The concept of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) serves as a fundamental measure in health economics, providing a standardized way to evaluate health outcomes and facilitate resource allocation decisions across diverse medical interventions. This metric allows policymakers, clinicians, and researchers to compare the effectiveness of treatments by combining both the quantity and quality of life into a single, comprehensible figure. As healthcare systems increasingly incorporate innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence, understanding how QALYs function becomes essential, especially when considering the broader implications for healthcare efficiency and ethical considerations.

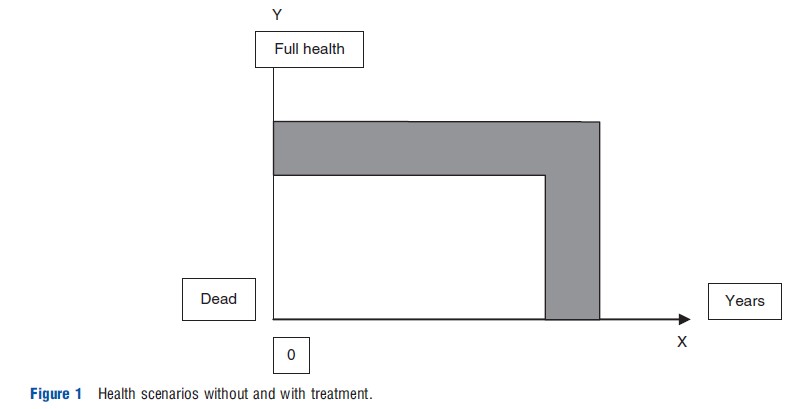

QALYs are designed to quantify health outcomes by integrating the length of life with the quality of health experienced during that time. The background for this measure is often illustrated through diagrams that depict how health status varies over time. For example, in a typical illustration, the X-axis represents the duration of life, while the Y-axis indicates health quality on a continuum from death to full health. The lower line in such a graph might show the health trajectory of a patient receiving standard treatment, whereas an upper line could represent an improved health outcome achieved through an alternative, more effective intervention. The area between these two lines signifies the total health gain, encompassing both improvements in life expectancy and health quality. The primary goal of the QALY is to consolidate these benefits into a single metric, making it easier to compare different health outcomes and interventions directly. This process involves technical methods explained in sections like “Definition, Operationalization, and Meaning.”

In health economics, the value assigned to a health outcome measured in QALYs can be related to the associated costs through what is known as the cost-effectiveness ratio. Often called a cost-utility ratio, this measure assesses the value for money of various health interventions. By calculating the cost per QALY gained, decision-makers can compare the efficiency of different treatments across medical fields, even when outcomes are of different types. These ratios assist in setting priorities and allocating limited healthcare resources more effectively, ensuring that funds are directed toward interventions that yield the greatest health benefits relative to their costs. To deepen understanding of how digital advancements like AI are transforming healthcare delivery, one can explore what is AI healthcare.

Definition, Operationalization, and Meaning

In the QALY framework, one full year of life in perfect health is used as the baseline, often termed a ‘well-year.’ Gaining one well-year equates to earning one QALY. The core idea is that any health outcome—regardless of its nature or magnitude—can be expressed as a fraction or multiple of a well-year, facilitating comparison. For example, a health state with a quality of life value of 0.8 implies that each year spent in that state yields 0.8 QALYs. This valuation reflects the health-related quality of life, which is typically scaled from zero (representing death or health states as undesirable as death) to one (full health).

These values are derived through psychometric methods and are used to weight life years in less-than-ideal health scenarios. The calculation involves summing the weighted years over the entire period of interest. For instance, if an individual lives for three years with health state values of 0.8, 0.6, and 0.5, their total QALYs would be 1.9 (i.e., 0.8 + 0.6 + 0.5). Similarly, gaining ten years in a health state valued at 0.6 results in 6 QALYs (10×0.6), while twelve years in a full health state yield 12 QALYs. Improving health from a lower to a higher state for one year might produce a gain of 0.2 QALYs, which over ten years amounts to 2 QALYs—equivalent to two years of perfect health. These calculations highlight how QALYs serve as a quantitative measure of health benefits that can be directly compared across different scenarios.

Estimating individual utility values involves complex methodological issues. These valuations are often obtained by asking representative samples of the general population to judge the severity of various health states, a process known as decision utility. Alternatively, patients and individuals with disabilities can provide experience-based utility assessments, which tend to reflect personal perceptions of their health states more directly. An insightful resource on how AI is reshaping healthcare delivery can be found at what is AI healthcare.

The utility values assigned to health states must have interval scale properties, meaning that equal changes in the utility score should represent equal differences in perceived health quality, regardless of the starting point on the scale. Preference elicitation techniques vary in their ability to produce utilities with these properties. Moreover, the calculation of QALYs assumes a linear relationship between health state duration and utility, implying that spending more time in a particular health state increases the total QALYs proportionally. However, real-world evidence suggests that individuals may experience diminishing marginal utility with longer durations in certain health states, leading to the practice of discounting future QALYs to reflect the preference for immediate health benefits.

Interesting:

- Understanding continuing education units ceus and their role in professional development

- Understanding healthcare performance metrics and their role in improving care

- Understanding healthcare management service organizations msos and their role in modern medical practices

- Understanding healthcare providers and their role in insurance

Another simplification within the QALY approach is the attribution of a single, fixed value to each health state, regardless of individual differences or contextual factors. This means that the disutility of, for example, dependence on eyeglasses, is considered equally undesirable for a young adult and an elderly person, ignoring the capacity to adapt over time. Critics argue this overlooks important nuances, such as how aging or personal circumstances influence health valuations. Similarly, the model assumes that the utility of a health state does not depend on the duration or cause, which may not always align with individual experiences. For instance, the utility of living with a disability might differ based on whether it was caused by an accident or congenital condition, but the standard QALY approach treats these states equivalently.

QALYs are often linked to expected utility theory, a normative framework for decision-making under uncertainty, formalized by von Neumann and Morgenstern in 1944. These principles underpin the rationale for aggregating health benefits across populations and for applying consistent valuation methods. Various techniques such as the standard gamble, time trade-off, and rating scales are employed to elicit health state utilities, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Empirical research has shown systematic differences between these methods, fueling ongoing debates about their relative validity in capturing true preferences. The interpretation of health state values as personal utilities remains contentious because the measurement process involves complex assumptions and simplifications.

Furthermore, the simplistic treatment of health benefit duration—simply counting years without considering individual preferences—has led some scholars to view QALYs more as indicators of health effect size rather than precise measures of personal utility. Despite criticisms, QALYs continue to serve as a practical tool for assessing healthcare efficiency, although ethical debates persist. Critics argue that the reliance on QALYs may favor individuals with a higher potential for benefit, potentially marginalizing the worse-off or those with chronic disabilities. Nonetheless, the core purpose remains to evaluate and compare health interventions systematically, aiding in making informed decisions about resource distribution.

Historical Development

The QALY concept emerged in the mid-20th century, with early precursors dating back to studies by Herbert Klarman and colleagues in 1968, who evaluated treatments for chronic renal disease using life years adjusted for quality of life. In the early 1970s, researchers like Anthony Culyer and George Torrance proposed new measures to better capture dysfunction-free years and health-related quality of life. The term “quality-adjusted life-year” appeared independently in 1976 in publications by Weinstein and Stason, and by Zeckhauser and Shepard, marking a significant milestone in health economics. These foundational works laid the groundwork for the widespread adoption of QALYs in clinical and policy evaluation, including influential papers such as Williams’ 1985 study in the British Medical Journal.

A comprehensive review of cost-effectiveness studies reported that the number of publications using QALYs has increased dramatically since the late 20th century, with hundreds of studies analyzing the economic value of health interventions worldwide. This growing body of research supports the use of QALYs as an essential component in health technology assessments and policy decision-making.

Alternatives to QALYs

While QALYs dominate the landscape of health outcomes measurement, alternative approaches have been proposed. The disability-adjusted life year (DALY), developed by Christopher Murray and colleagues, is a prominent example. Unlike QALYs, which use a utility scale from zero to one, the DALY employs a severity scale from zero (full health) to one (dead), emphasizing the burden of disease rather than individual preferences. Primarily designed for global health assessments, the DALY has found extensive application in evaluating health programs, particularly in developing countries.

Another notable alternative is the “save” concept proposed by Erik Nord, which shifts focus from life years and their quality to the moral claims of living individuals. The saved young life equivalent (SAVE) measures societal value by the importance placed on saving young lives and restoring individuals to full health. Although promising in theory, the SAVE approach has seen limited practical application in economic evaluations to date. For further insights into emerging health measurement techniques, explore why data security matters in healthcare.